‘One of the reasons why I chose the pseudonym of James Bond for my hero rather than, say, Peregrine Maltravers was that I wished him to be unobtrusive. Exotic things would happen to and around him but he would be a neutral figure – an anonymous blunt instrument wielded by a Government Department.

But to create an illusion of depth I had to fit Bond out with some theatrical props and, while I kept his wardrobe as discreet as his personality, I did equip him with a distinctive gun and, though they are a security hazard, with distinctive cigarettes. This latter touch of display unfortunately went to my head. I proceeded to invent a cocktail for Bond (which I sampled several months later and found unpalatable), and a rather precious though basically simple meal ordered by Bond proved so popular with my readers, still suffering from war-time restrictions, that expensive, though I think not ostentatious, meals have been eaten in subsequent books.The gimmickry grew like bindweed and now, while it still amuses me, it has become an unfortunate trade-mark… However, now that Bond is irretrievably saddled with these vulgar foibles, I can only plead that his Morland cigarettes are less expensive than the Balkan Sobranie of countless other heroes, that he eats far less and far less well than Nero Wolfe, and that his battered Bentley is no Hirondelle…’1

So wrote Ian Fleming to the Manchester Guardian in April 1958, responding to a slew of attacks on his work in the previous few weeks. It’s a revealing letter in several ways, but most striking, I think, is the last paragraph I’ve quoted, where he shows that he had a firm knowledge of the thrillers that had come before him (even if he misspelled The Saint’s car), and points out that many of the criticisms of his novels could equally be applied to those written by earlier authors. Implicit in this is the accusation that those attacking his work didn’t seem particularly familiar with the conventions of the thriller genre.

When the first James Bond novel, Casino Royale, was published in 1953, it had a lot of competition for the public’s attention, with dozens of other thriller-writers seeking a similar audience; only a clairvoyant would have been able to tell that the hero of the book would become an iconic fictional character for the ages. Alan Ross’ review in The Times Literary Supplement four days after the novel was published was titled ‘Espionage in the Sapper manner’, and noted the similarities and differences between it and H. ‘Sapper’ McNeile’s Bulldog Drummond books:

When the first James Bond novel, Casino Royale, was published in 1953, it had a lot of competition for the public’s attention, with dozens of other thriller-writers seeking a similar audience; only a clairvoyant would have been able to tell that the hero of the book would become an iconic fictional character for the ages. Alan Ross’ review in The Times Literary Supplement four days after the novel was published was titled ‘Espionage in the Sapper manner’, and noted the similarities and differences between it and H. ‘Sapper’ McNeile’s Bulldog Drummond books:'Mr. Ian Fleming’s first novel is an extremely engaging affair, dealing with espionage in the Sapper manner but with a hero who, although taking a great many cold showers and never letting sex interfere with work, is somewhat more sophisticated. At any rate he takes very great care over his food and drink, and sees women’s clothes with an expertness of which Bulldog Drummond would have been ashamed. The main plot of Casino Royale deals with the attempt of a British agent to outgamble a Communist agent whose sexual predilections have cost him a lot of money and who must play for high stakes to make up the Party funds and carry out his programme. The game concerned is baccarat and the especial charm of Mr. Fleming’s book is the high poetry with which he invests the green baize lagoons of the casino tables. The setting in a French resort somewhere near Le Touquet is given great local atmosphere and while the plot itself has a shade too many improbabilities the Secret Service details are convincing. Altogether Mr. Fleming has produced a book that is both exciting and extremely civilized.'2

Fleming cherished this review, perhaps partly because he had long been an admirer of the TLS, and knew it awarded him significant literary status to be reviewed in it.3 The review is also perceptive about what Fleming was trying to do with the novel, and highly flattering to boot. Ross was right to point out that Casino Royale was an attempt to add sophistication to the heroic tradition Sapper was part of, but he could just as well have written about the Sax Rohmer manner, or the Valentine Williams manner, or one of a number of others – the novel isn’t especially in debt to Sapper. Ross may have mentioned him simply because he was more familiar with his work than others in the genre: in his memoir Blindfold Games, published in 1986, he wrote that his ideals ‘had once been AJ Raffles, amateur cracksman and cricketer – at least the initials were the same – The Saint and Bulldog Drummond, and even more so their originators.’4

Fleming cherished this review, perhaps partly because he had long been an admirer of the TLS, and knew it awarded him significant literary status to be reviewed in it.3 The review is also perceptive about what Fleming was trying to do with the novel, and highly flattering to boot. Ross was right to point out that Casino Royale was an attempt to add sophistication to the heroic tradition Sapper was part of, but he could just as well have written about the Sax Rohmer manner, or the Valentine Williams manner, or one of a number of others – the novel isn’t especially in debt to Sapper. Ross may have mentioned him simply because he was more familiar with his work than others in the genre: in his memoir Blindfold Games, published in 1986, he wrote that his ideals ‘had once been AJ Raffles, amateur cracksman and cricketer – at least the initials were the same – The Saint and Bulldog Drummond, and even more so their originators.’4It might also have been a result of expectations. Ross, a poet, was a friend of Fleming’s wife, Ann, and so counted as ‘family’, and Ian Fleming was well known in journalistic circles as an elegant and fastidious dresser concerned with the finer things in life. He wrote the Sunday Times column Atticus and was a member of Boodle’s, the exclusive gentlemen’s club in Pall Mall, where he would sometimes sit and read thrillers quietly in a corner. The idea that Ian Fleming had written a thriller in the Sapper mould fitted the image of the man, if not quite the image of the novel. This can be seen in the first published parody of James Bond. His Word, His Bond by ‘Ixn Flxmxng’ – in fact, Fleming’s colleague at Atticus, John Russell – appeared in The Spectator in December 1956:

'Chapter XIX

YMCA Again!

The whole room smelt of the Mexican.

‘Take him away,’ said Bond, as he straightened his old Mauresque’s tie. ‘His igguda’s broken. It’s a trick I learned from the YMCA.’

The YMCA! Ensign Squarehead’s eyes narrowed at the mention of the Soviet Counter-counter-under-the-counter group.

‘Where’ll I put him, Boss?’

‘Down the lift-shaft,’ said Bond. The traffic would cover the scream.

As Squarehead made off with his twitching burden, Bond turned to the internal television apparatus.

‘Canteen,’ he said evenly, and one of the most beautiful women he’d ever seen stood before him on the cazonated uviform frumpiglass screen.

‘Two double Martinis,’ said Bond, specifying the Old Fusty and a dash of Miss Dior.

As the woman bent over her blotter the sun sparked on her spectacles (‘f.9/34 Spitzer Weichmann lenses,’ Bond noted automatically). The wind from the open window stirred the blue ridge of her facial hair, there was pre-stressed concrete in the bridge of her nose, and her 1294 mm. bust lay like an unwrapped parcel on the top of her desk. She reminded him of something he’d once seen by Rembrandt, the artist.

One day he’d take her away from this filthy business. There’d be a seat for her on the racing tricycle that old W.O. Bentley had built for him with his own hands in the bad year before Munich. They’d pedal down N.63… And he’d see how she shaped.

‘Shaped?’ He was forgetting himself. ‘And get me something to eat.’

‘The usual, Commander?’ Her nostrils showed the admiration she felt, in spite of herself, for the trim, slim man with the pressurized waistcoat and the ankles of a gambler.

‘Hippo steaks,’ said Bond, ‘with a double portion of Mobiloil dressing. Those mussels you get for me from Danzig, with some chopped rhinestones. No béarnaise, of course, but some very fresh okapi trotters, boiled in Jordan water, and a carton of Old Hatstand crackers.’

The simple meal was nearly finished when the blood-red telephone went galloo-galloo.

‘B.,’ said the familiar voice; and Bond leant forward on his malleable inscuffated drabba-tested gros-point cuffs.

‘Would you know Blotkin-Plotkin if you saw him?’

‘The YMCA chief?’ said Bond. ‘The hunchbacked seven-foot negro with the long red beard and nine fingers to his right hand? I don’t think I’d mistake him.’Perhaps it’s unfair to give too much thought to an ephemeral piece of fun written over half a century ago, but it’s striking just how wrong this parody gets James Bond. There are some great touches, such as the spot-on first sentence, which could almost be out of a Fleming novel, as well as Bond’s prissiness and the authoritative use of precise terms about the tiniest of matters. But it doesn’t read as though it has been written by someone who knows Fleming’s novels, or has even read them. The main reason most of it isn’t very funny is because it doesn’t seem anything like a Bond novel. Despite a few modern and even futuristic ideas, as a whole it feels more like a parody of thrillers from the Twenties or even earlier, with telephones going ‘galloo-galloo’. The inclusion of an aide/batman for the hero is completely out of character for Fleming: they were a staple of earlier thrillers, but there is no such figure in the Bond novels.

‘He’s in Surrey again. I told the PM I could count on you.’

All tiredness forgotten, Bond called to his aide.

‘Leatherhead, Squarehead,’ he said evenly.

The fight was on.'5

But all this was still a few years away, when Fleming was on the verge of best-sellerdom. In April 1953, he was just embarking on the journey. The reviews for Casino Royale in the Times Literary Supplement and several other well-respected publications were coups for a debut thriller, but they had come about in large part because Fleming was exceptionally well connected: he was a journalist at the country’s most prestigious newspaper, his brother Peter was a famous writer, and his wife was a noted literary hostess who had been married to the press magnate Viscount Rothermere. Casino Royale was also positively reviewed in the Daily Telegraph by the poet John Betjeman, another friend, but the most favourable review appeared, unsurprisingly, in the paper Fleming wrote for, the Sunday Times. Written by Cyril Ray under the pseudonym Christopher Pym, it also sought to put the debut thriller into context:

'Here is a new writer who takes us back to the casinos of Le Queux and Oppenheim, the world of caviar and fat Macedonian cigarettes. But with how much more pace in the writing, how much less sentimentality in the tone of voice, how much more knowing a look!... From the first evocative words to the last savagely ironic sentence, this is a novel with its own flavour and its own startlingly vivid turn of phrase… If Mr Fleming’s next story has half the swiftness of this, as astringent an accent, and a shade more probability, we can be certain that here is the best new English thriller-writer since Ambler. One is pretty certain already.'6

By 1953, the British spy thriller had already forked into two fairly distinct sub-genres. The genre’s first major practitioners, William Le Queux and E. Phillips Oppenheim, had frequently written about heroic upper-class British secret agents battling monstrous foreign villains – usually German – in glamorous hotels and casinos around Europe. They had been followed by the likes of John Buchan, Valentine Williams, Alexander Wilson, Sapper and several others, which we could loosely call the heroic school. In 1928, Somerset Maugham had shaken up the genre with Ashenden, which presented espionage as a much more complicated and uncertain business. In the 1930s, writers like Eric Ambler and Graham Greene took up Maugham’s mantle. This school, which we could perhaps call the realistic tradition, would, in the 1960s, see the emergence of John le Carré and Len Deighton.

By 1953, the British spy thriller had already forked into two fairly distinct sub-genres. The genre’s first major practitioners, William Le Queux and E. Phillips Oppenheim, had frequently written about heroic upper-class British secret agents battling monstrous foreign villains – usually German – in glamorous hotels and casinos around Europe. They had been followed by the likes of John Buchan, Valentine Williams, Alexander Wilson, Sapper and several others, which we could loosely call the heroic school. In 1928, Somerset Maugham had shaken up the genre with Ashenden, which presented espionage as a much more complicated and uncertain business. In the 1930s, writers like Eric Ambler and Graham Greene took up Maugham’s mantle. This school, which we could perhaps call the realistic tradition, would, in the 1960s, see the emergence of John le Carré and Len Deighton.

Broadly speaking, writers of the heroic school favoured fast-paced plots over characterization and prose style and glamourized espionage, while writers in the realist school were more interested in internal action and the psychology of espionage, and tended to have a much greater flair with language. Writers such as Sapper and Rohmer were also regarded as somewhat ‘below stairs’, while Ambler and Greene were afforded more praise by the literary establishment.

Ian Fleming was a fan of both these schools of spy fiction. As a schoolboy, he had devoured the works of Sapper and Rohmer, but as an adult he was an admirer of Greene and Ambler. Fleming had set out to add some literary sophistication to the heroic spy thriller, adding a dose of grit to the glamour: Casino Royale plays out against a background of gambling for high stakes, exotic cocktails and beautiful clothes, but ends with the hero having his genitals tortured and being betrayed by the woman he wanted to wed. But it is a mistake to think that Fleming was the first to attempt this sort of thing. It is as though there is a gulf between the 1920s, when Sapper was at the peak of his success, and 1953. In fact, in those intervening years several writers tried to add a more sophisticated and convincing portrayal of espionage to thrillers in the heroic tradition, and a few succeeded in doing so.

Five months after Casino Royale was published, Richard Usborne’s Clubland Heroes appeared. This was a new type of literary criticism, a dry and witty look at three rather musty thriller-writers, all of them firmly in the heroic tradition. In time, these writers would come to be seen as pre-eminent influences on Fleming, and the phrase ‘clubland heroes’ would be linked to James Bond in dozens of articles and books:

'In 1953 two remarkable books were published. One was Casino Royale, a first novel by Ian Fleming – but more of that later. The other was a fascinating and extremely readable little volume entitled Clubland Heroes. Nothing quite like it had ever been done before. Its author, Richard Usborne, set out to examine certain of the writings and characters of three popular authors of his youth: John Buchan, Sapper and Dornford Yates.

It is significant that each of these best-sellers produced the bulk of his work in an era that was pre-1939, and it is no coincidence that they all dealt with characters who might collectively be termed Upper Class. In the 1960s – and, indeed, when Usborne wrote about them – they appeared more than a little archaic...

Ten main characters are placed under the microscope. With the exception of Carl Peterson, Sapper’s arch-criminal and one of the most infamous villains of sensational fiction, all are cast in the same mould. They are all West End clubmen, they all appear to be of independent means and they all conform to a rigid code of honour made up by equal parts of birth, public school, university and the army. They are all extremely masculine, virile and, paradoxically, utterly emasculated.

Of the ten characters examined, only three need concern us here. John Buchan will forever be associated with Richard Hannay; Sapper’s foremost hero is, of course, Bulldog Drummond, and Dornford Yates’ protagonist in this particular genre is undoubtedly Jonah Mansel: the Terrible Trio of popular fiction between the two wars. Millions of readers have thrilled to the exploits of these imaginary but none the less very real adventurers. But how do they stand up today beside Ian Fleming’s sophisticated and sardonic Secret Service agent, Commander James Bond?...

James Bond, like the Terrible Trio, is of the clubland stratum of society, if he is not exactly a hero. He is comfortably off, and always has been, even if he does a job of work too. He moves easily in places like the Ritz, the Hotel de Paris, and the sporting clubs and private rooms of continental casinos. He understands the code of people like Hannay, Drummond and Mansel, upheld to a large extent by M, his chief, who holds ‘a great deal of his affection and all his loyalty’, but he does not live by it…

It could be argued, of course, that I have snatched at the convenience of Usborne’s Clubland Heroes, and that they have little in common – even by comparison – with James Bond. I admit that he would probably be far more comfortable in the company of, say, Leslie Charteris’ Simon Templar, the Saint, from the little I know of that character. I know little of him because he seems to me a mere ghost, or at the most a lay figure jouncing and swashbuckling through an interminable number of books and stories which are forgotten almost as soon as they are read. Sensational fiction is full of slightly caddish protagonists, non-heroes who appear to be – on the face of things – closer to Bond than the illustrious triumvirate. These range from the gentleman-cracksman type like the early Raffles and the later Blackshirt to the tough, cynical Private Eye like Philip Marlowe and the hooligans of Mickey Spillane. It could be argued that Bond has more in common with any of these than with Hannay, Drummond and Mansel.

Personally, I don’t think he has. The Terrible Trio were alive. We can believe in them as real people, despite the outrageous adventures they all got up to…'7

So begins O.F. Snelling’s 007, James Bond: A Report, published in 1964. It’s an easily read book and is packed with well-observed and elegantly phrased insights into Ian Fleming’s work. But much in these opening pages is severely flawed. Yes, it could indeed be argued that James Bond had more in common with other protagonists than Richard Hannay, Bulldog Drummond and Jonah Mansel – and I’m damn well going to argue it!

There are several ideas here that simply don’t withstand analysis. Firstly, that the three thriller-writers Richard Usborne happened to enjoy most as a boy also created the three most celebrated heroes of popular fiction between the two wars. They were all hugely successful, but there were many others. Secondly, the proposition that the three writers Usborne chose to analyse just so happened to be the very three writers who most influenced Ian Fleming. The chances of that are slim, surely. And finally, the idea that Fleming was primarily influenced by pre-1939 British novels – why not American novels, or films, or Austrian ones for that matter (Fritz Lang comes to mind)? How about thrillers published after 1939?

Dornford Yates was the pseudonym of Cecil Mercer, a cousin of Saki. He wrote some very enjoyable thrillers, but Mansel isn’t one of the genre’s most memorable characters. He was introduced in 1914 in the collection of short stories The Brother of Daphne, where he is established as the quietest, most practical and most mysterious of a group of charmed and related upper class friends:

'Jonah rose, walked to the window, pulled the curtains aside, and peered out into the darkness.‘What of the night?’ said I.‘Doth the blizzard yet blizz?’ said Berry.‘It doth,’ said Jonah.'8

Mansel appeared in several of Yates’ books, but he’s often so peripheral to the action that it’s difficult to describe his character. We learn a few bare facts about him over the course of several adventures: he is a bachelor who lives in a flat in Cleveland Row, St. James, where he has a manservant called Carson. He smokes a lot (usually a pipe), and limps due to having been shot through the knee at Cambrai. He’s a very fast but careful driver, efficient, imperturbable (unless his old charger horse Zed is involved) and has unspecified connections with the intelligence world. But that’s about as far as one can go with Jonah Mansel, and there is little to distinguish him from dozens of other characters in thrillers of the era. Perhaps his most Bond-ish moment comes in Cost Price, published in 1949, in which he and his friends hide some jewels that once belonged to the Borgias in a secret locker in his Rolls Royce.

Mansel appeared in several of Yates’ books, but he’s often so peripheral to the action that it’s difficult to describe his character. We learn a few bare facts about him over the course of several adventures: he is a bachelor who lives in a flat in Cleveland Row, St. James, where he has a manservant called Carson. He smokes a lot (usually a pipe), and limps due to having been shot through the knee at Cambrai. He’s a very fast but careful driver, efficient, imperturbable (unless his old charger horse Zed is involved) and has unspecified connections with the intelligence world. But that’s about as far as one can go with Jonah Mansel, and there is little to distinguish him from dozens of other characters in thrillers of the era. Perhaps his most Bond-ish moment comes in Cost Price, published in 1949, in which he and his friends hide some jewels that once belonged to the Borgias in a secret locker in his Rolls Royce.  In my last post, Conventional Thinking, I discussed Leslie Charteris’ novel Knight Templar, published in 1930, in which an ugly giant who is also one of the richest men in the world is intent on starting a European war. He captures The Saint and foolishly tells him what he is planning to do, even while he is pontificating about the fact that he’s not going to make the mistake common in popular thrillers of devising a method of death so elaborate and complicated that The Saint will easily escape from it. I pointed out that earlier in the novel The Saint used a cigarette fitted with a magnesium flare to escape captivity – a device that James Bond wishes he has in From Russia, With Love when in a similar position. The Saint also sometimes works for the British secret service, takes on American gangsters in New York, is a dashingly handsome connoisseur of food and wine, is always immaculately dressed, has black hair, blue eyes, a tanned complexion, a bullet scar through his left shoulder and another scar on his right forearm, carries firearms, is an expert knife-thrower, and speaks several languages.

In my last post, Conventional Thinking, I discussed Leslie Charteris’ novel Knight Templar, published in 1930, in which an ugly giant who is also one of the richest men in the world is intent on starting a European war. He captures The Saint and foolishly tells him what he is planning to do, even while he is pontificating about the fact that he’s not going to make the mistake common in popular thrillers of devising a method of death so elaborate and complicated that The Saint will easily escape from it. I pointed out that earlier in the novel The Saint used a cigarette fitted with a magnesium flare to escape captivity – a device that James Bond wishes he has in From Russia, With Love when in a similar position. The Saint also sometimes works for the British secret service, takes on American gangsters in New York, is a dashingly handsome connoisseur of food and wine, is always immaculately dressed, has black hair, blue eyes, a tanned complexion, a bullet scar through his left shoulder and another scar on his right forearm, carries firearms, is an expert knife-thrower, and speaks several languages.

I think The Saint is significantly closer in conception to James Bond than Bulldog Drummond, Jonah Mansel or Richard Hannay.

That Charteris is so rarely mentioned as an influence on Fleming is perhaps related to his prolific output: I think there is a tendency to feel, as Snelling did, that any series with so many entries can’t be all that worthwhile. But Charteris was a magnificent and innovative writer, and he maintained a very high standard throughout the series. The Saint was also much better known than at least one of the ‘Terrible Trio of popular fiction between the two wars’. Dornford Yates was a best-selling author, but Jonah Mansel never achieved the level of popularity of The Saint:

'In 1930, the major thriller publishing house of Hodder & Stoughton threw itself solidly behind the Saint. Launching him with the most lavish fanfare ever accorded a fictional hero, they claimed ‘the man who has never heard of the Saint is like the boy who has never heard of Robin Hood’'.9By the time Casino Royale was published in 1953, 29 Saint books had been published, and there had been eight very successful films featuring the character. Jonah Mansel had appeared in 15 books, but was often a peripheral character and rarely the outright protagonist.

In the 1950s, Kingsley Amis was a friend of Richard Usborne, who was a fellow member of the Garrick, and they were later neighbours in Hampstead.10 In his study of Ian Fleming’s work, The James Bond Dossier, published a few months after Snelling’s book, Amis also drew much of his tone from Usborne’s Clubland Heroes, which he called informative, entertaining and required reading for students of the genre.11 All of which is true – but it doesn’t replace reading the genre.

Amis and Snelling’s books were both very successful: Snelling’s sold over a million copies.12 Perhaps partly as a result, the connection between James Bond and the clubland heroes has been made repeatedly since, sometimes in the strangest of ways. Reviewing Andrew Lycett’s biography of Ian Fleming in 1995, Michael Davie wrote:

'But for his phenomenal success with Bond, Fleming’s life would be of scant interest. As it is, 007 is lodged somewhere inside all our heads, together with an uneasy feeling that the appeal of his crude clubland values and sado-masochism tells us something disreputable about ourselves.'13While reviewing Jeremy Black’s book The Politics of James Bond in 2002, Jeffrey Richards commented on Fleming’s novels:

'For those raised exclusively on the Bond films – with their unbeatable blend of conspicuous consumption, brand-name snobbery, technological gadgetry, colour-supplement chic, exotic locations and comic-strip sex and violence – it is instructive to return to the earlier novels, which, with their clubland ethos, casual racism, preoccupation with the Soviet threat and references back to the war, are closer in tone to Sapper and John Buchan than the ‘swinging Sixties’ era of the first films.'14But conspicuous consumption, brand-name snobbery, technological gadgetry, exotic locations and comic-strip sex and violence can also be found in all of Fleming’s novels – and, indeed, in dozens of other British thrillers, from about 1895 onwards. I think Ian Fleming would have been aware of many of them: perhaps something closer to a Terrible Thirty than Snelling’s Terrible Trio. Fleming was a thriller aficionado:

‘There aren’t enough good thrillers for me – I like reading them in aeroplanes and trains. I find they’re wonderful kind of books to pass the time with.’15

So which thrillers might Fleming have been reading in planes and trains prior to writing Casino Royale? Well, certainly Buchan and Sapper, as he discussed both in interviews and mentioned Bulldog Drummond in several novels. Perhaps also Dornford Yates, but I think if there was an influence it was probably slight. Because the thriller was a very crowded field. Fleming might, for example, have enjoyed the novels of Francis Beeding, a pseudonym for two writers, Hilary Saunders and John Palmer. Between 1928 and 1946, they published 18 thrillers featuring spymaster Colonel Alistair Granby, Toby to his friends, PB3 to British intelligence.

Another very successful series was by Manning Coles – also a pseudonym for two writers – featuring their character, British secret agent Tommy Hambledon. After being struck on the head on a mission in the First World War, Hambledon loses his memory, only to recover it once he has risen through the ranks of the Nazi party, after which he resumes contact with British intelligence. Hambledon featured in 25 novels, published between 1940 and 1963.

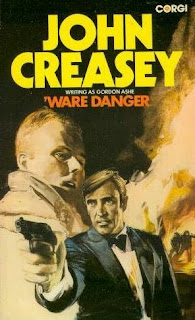

The astonishingly prolific John Creasey also wrote spy thrillers, using the pseudonym Gordon Ashe. Colonel Patrick Dawlish featured in 50 novels between 1939 and 1975, with his role at various times being that of a daring vigilante, a secret agent behind enemy lines and a senior detective at Scotland Yard. Some of the later editions of this sort of thriller were shameless in stressing the similarities with the character they predated: in 1972, Corgi gave a new edition of ’Ware Danger, first published in 1941, a jacket that blatantly adapted artwork used for the film Diamonds Are Forever the previous year, with Colonel Dawlish as a Sean Connery figure on a particularly bad wig day.

Fleming might have been tickled by the idea of reading thrillers with a character who shared his surname: Simon Harvester’s series featuring British spymaster Roger Fleming began with Let Them Prey in 1942, and the seventh novel was published in January 1951.

Or perhaps he enjoyed Desmond Cory’s series about freelance secret agent Johnny Fedora, which began with Secret Ministry, also published in 1951.

There were a lot of thrillers in this vein, most of them now forgotten and rarely examined. Very few of them were reviewed in the Times Literary Supplement or the Sunday Times, but then very few were written by journalists on the staff of the latter. Critics reading Sapper, Buchan or Yates novels as a result of comparisons made by Alan Ross, O.F. Snelling, Kingsley Amis or others will certainly have found similarities with Ian Fleming’s work, but I think many have been misled. Some, predisposed to finding merit in Fleming’s work, have noted how old-fashioned a few novels written in the 1920s were in comparison with Fleming’s, which were written three or four decades later. This focus on such a narrow field of influences has led to the idea that Fleming originated most of the conventions of the genre established in the early part of the 20th century, as well as several that emerged during and after the Second World War.

There were a lot of thrillers in this vein, most of them now forgotten and rarely examined. Very few of them were reviewed in the Times Literary Supplement or the Sunday Times, but then very few were written by journalists on the staff of the latter. Critics reading Sapper, Buchan or Yates novels as a result of comparisons made by Alan Ross, O.F. Snelling, Kingsley Amis or others will certainly have found similarities with Ian Fleming’s work, but I think many have been misled. Some, predisposed to finding merit in Fleming’s work, have noted how old-fashioned a few novels written in the 1920s were in comparison with Fleming’s, which were written three or four decades later. This focus on such a narrow field of influences has led to the idea that Fleming originated most of the conventions of the genre established in the early part of the 20th century, as well as several that emerged during and after the Second World War.

Others (a wider group), predisposed to finding flaws in Fleming’s work, have noted the racism and sexism in Buchan and Sapper and simply transposed it to the Bond novels. From this a strand of criticism has emerged that claims that Fleming’s novels glorify an imperialist crypto-fascist psychopathic murdering rapist – this is currently a mainstream view of the work of one of the 20th century’s finest popular writers. It was helped along significantly by Paul Johnson’s famous attack on Dr No in The New Statesman in 1958, the title of which – ‘Sex, Snobbery and Sadism’ – has alone been used as shorthand by lazy critics to write off Fleming ever since. I’ll tackle Johnson’s critique in one of the next posts in this series, but first I’ll look at some writers whose influence on Ian Fleming has not been discussed because of the over-emphasis on John Buchan, Sapper and Dornford Yates.

References

1. Letter from Ian Fleming, Manchester Guardian, April 5 1958.

2. ‘Espionage in the Sapper manner’ by Alan Ross, Times Literary Supplement, April 17 1953.

3. In his introduction to the 1963 reissue of Hugh Edwards’ All Night at Mr. Stanyhurst’s, Fleming wrote that an essential item in his ‘Desert Island’ library would be the Times Literary Supplement, ‘dropped to me each Friday by a well-

4. p154, Blindfold Games by Alan Ross, Collins Harvill, 1986.

5. His Word, His Bond by ‘Ixn Flxmxng’, pp80-81 Spectrum: A Spectator Miscellany, 1956, Longmans, Green & Co.

6. ‘Cards on the table’ by Christopher Pym, Sunday Times, April 12 1953.

7. pp11-15 007, James Bond: A Report by O.F. Snelling, Panther, 1965.

8. p67, The Brother of Daphne by Dornford Yates, BiblioBazaar, 2008.

9. p18, The Saint: A Complete History in Print, Radio, Film and Television of Leslie Charteris’ Robin Hood of Modern Crime, Simon Templar 1928-1992 by Burl Barer, McFarland, 2003.

10. Personal communication with David Usborne (son of the author), November 22, 2007.

11. p66 The James Bond Dossier by Kingsley Amis, Signet, 1966.

12. Obituary of O. F. Snelling, The Independent, January 31 2002.

13. ‘Ian Fleming: gin, golf clubs, and men – A vulgarian in clubland’ by Michael Davie, Times Literary Supplement, December 1 1995.

14. ‘Britannia is forever in 007’s film world’ by Jeffrey Richards, Times Higher Education, January 18 2002.

15. Ian Fleming in conversation with Raymond Chandler, Third Programme, BBC Home Service, July 10 1958.

This is part of 007 In Depth, a series of articles on Ian Fleming and James Bond.

...and, who exactly is this "popular writer" you refer to? ;-)

ReplyDeleteWell I never thought I’d read that Fleming found the Vodka Martini (or was it the Vesper he was referring to?) unpalatable; can’t say I have ever seen that in print before. Also the lengths Fleming went to defend his work i.e. The Manchester Guardian. I think it’s quite an interesting insight into Fleming as a Writer. Proof he was only human and at times felt the need to defend his work.

ReplyDeleteMakes one ponder if Fleming wasn’t so well connected as the article points out, would he have been as successful as he was?

The Clubland reference is one that I never understood until this article. The reference ‘clubland’ for me was a bit like laughing at a joke I didn’t get. Great detective work as always and a joy to read what Fleming could have been reading thriller-wise, do you think Fleming would still have read Sapper in adult life? You have opened up some fresh thinking on Fleming here I think, and I agree it’s a shame that the critics have been lazy in regards Fleming over the years. I look forward to your look at the “Sex, Snobbery and Sadism” critique in the future. It’s been an education. I am as guilty as the next man for accepting what the critiques say as the truth. It’s scary that it gets burned into folk-law.

The new search tool has made The Debrief very user friendly.

Matthew, I think it was some chap called Fleming. :)

ReplyDeleteNick, thanks for the comments. I think Fleming was referring to the Vesper there - but funny that he didn't like it. The excerpt I've quoted from the letter is about a third of it - I'll probably discuss other parts of it later. It was quite a long letter, but then he had just been attacked from several angles. There were serious apects to the critiques, but I think on the whole they were attacks more than critiques, alleging he was immoral and so on.

The search tool was always there but it had been tucked away at the foot of the page and I only just spotted it myself the other day. I thought I'd move it up where people can see it and hopefully use it. :)

You don't touch much on the Buchan/Hannay influence.

ReplyDeleteI had the occasion to read all the Hannay novels over a very short period of time, in Penguin's omnibus edition.

What interested me is how different THE THIRTY-NINE STEPS is from the following books. The Hannay of that book is not a clubman, not upper-class (he's a mining engineer gone off to South Africa to make a living), and indeed is so ill connected that his run across Great Britain has to be done unassisted. It's a great book, and Hitchcock's movie of it is very true to it (tho' many details are altered; my favourite alteration, of course, is making Hannay a Canadian :-).

The Hannay of THE THIRTY-NINE STEPS would never be a Bond- (or Drummond- or Templar-) like hero. His later incarnations, though - a wealthy landowner who rocketed through the ranks in the Great War - has no connection in spirit to the lost, friendless, resourceful Hannay of the first novel.

(Incidentally, Buchan, in his alter ego of the Conservative peer Lord Tweedsmuir, became Governor General of Canada, and founded the GG's Awards for Literature, which are a fixture in Canada's literary calendar.)

Rick, thanks very much for the comment. No, I haven't touched much on the Buchan influence, because I think it is completely overblown. I think it's clear that Fleming would have read Buchan, and that he would have been an influence, because he was one of the most successful thriller writers of the age. But I don't buy that Buchan was a *key* influence on Fleming, which is the claim that is usually made. And usually made, I should say, with no backing to it whatsoever. Your post here is more detailed and convincing than any article or piece of criticism I've read on Buchan and Fleming.

ReplyDeleteI think there are certain conventions Buchan helped solidify, such as the secret organizations plotting to change the world, and that broadly speaking Buchan featured upper-crust British heroes stopping such plots. But I think other writers were much greater influences on him. For example, Geoffrey Household, who took Buchan's chase thriller and, um, ran with it. I can think of several ideas and incidents in Fleming novels that directly parallel Household, to the point that common sense dictates he was the influence. I can't think of any for Buchan. In addition, we know that Fleming was a Household fan.

I'll tackle Buchan and Household in a later post. If you read the posts in this series before and after this one, Conventional Thinking and Bloods Line, you'll get more of an idea why I think Buchan is something of a red herring.

And thanks again for commenting - nice to see you here!

My apologies about dredging up an old blog post, but I don't think the following comment could go anywhere else. I was recently reading an essay by Clive James called "Starting with Sludge," about James's childhood reading, and how it progressed as he moved toward adolescence. After going through stuff like the Biggles books, Ellery Queen, and Erle Stanley Gardner, James reaches a higher level with a certain Mr. Charteris. I'll let him take it from here:

ReplyDelete"I bought every Saint book in print...There was no room to arrange all my Saint books on my bed, so I lined them up in rows on the lounge room floor, in front of the Kosi stove: Enter the Saint, The Saint Steps In, The Saint Closes the Case and (wait for it: the title of the century) The Last Hero. Bliss! And boy, couldn’t Leslie Charteris write, I asked my mother rhetorically, quoting the evidence by the page while she dusted the wax fruit in the brass dish. For the first time in my career as a reader, here were sentences which, when you read them again, got better instead of worse.

"Even more than Bulldog Drummond, the Saint was a model for James Bond: years later, I could tell from the first pages of Ian Fleming that he, too, had once thrilled to Simon Templar’s savoir faire, his Lobb shoes, his upmarket mistress and his mighty, hurtling Hirondel —a car that would have seen off Bond’s Bentley in nothing flat. Unlike Drummond, the Saint, though he packed a narcotic uppercut and could shoot the pips out of the six of diamonds after flicking it through the air, existed on the level of mentality: he was clever, he had wit. He didn’t just charge and shoot, he figured things out, like Sanders of the River but without the solar pith helmet. For someone like me-—someone who was bringing exactly no sporting trophies home from school, and for whom a reasonable result in English was his sole academic distinction-— the idea that brains could be adventurous was heady wine."

James later writes that Conan Doyle, Charteris, and C.S.Forester could each be described as "too good a technician to be classified as a sludge writer tout court."

I'm sure James's guess about the influence of Charteris on Fleming will bring a smile to your lips. The full essay can be read at: http://www.clivejames.com/articles/clive/sludge

I know you're not American, but the weather is so uncharacteristically nice here in San Francisco that I can't help wishing you a happy Fourth of July!